This is the second entry in our new series, TIKKUN OLAM. In it, we intend to explore what justice looks like in the eyes of God, and how we are called to partner with God in the healing of the world. We began by recognizing that the cry for justice does not begin with practical solutions, but grief that things are not as they should be, the way God desires them to be.

The pursuit of justice begins with a deep conviction that God created the world and called it all “good”. What we are talking about here is the age-old question of theodicy, which means “the vindication of God”. If God is all-good and all-powerful, how do we frame the problem of evil? Does God cause or allow evil to exist, and what is God doing about it? And how does defining good and evil posture us to understand the call to justice correctly? There is a reason we have not settled on air-tight solutions for the problem of evil in the course of two thousand years of Church history. Few theories are ever satisfying and all-encompassing when we engage with Mystery. However, I consider there to be a couple particular frames that will help us get closer to truth in our pursuit of justice.

In the beginning God speaks creation into existence, from Mind to Word to Matter. The Genesis poem uses the word “let”, as if God is granting permission for existence to pour forth. First, realms are separated out and defined - light/dark, sky, land/sea. Then they are filled in with good things - plants, sun and moon, fish, birds, livestock, and eventually us. The poem’s intention is to show us how God creates, not out of strife or ambivalence, but an overflowing joy as ever-increasing diversity unites in harmony. Along the way God declares everything created “good”, which we might define as the inherent “god-ness” in created things. As creation flourishes, so God’s glory is revealed. “For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made…” (Rom. 1:20).

The last few verses in the poem, however, contain a semantic oddity:

By the seventh day God had finished the work he had been doing; so on the seventh day he rested from all his work. Then God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it he rested from all the work of creating that he had done. (Gen. 2:2,3)

The final phrase breaks down like this in Hebrew:

asher | bara | elohim | la’asot

which | created | God | to do

The final word, meaning “to do” or “to make”, feels redundant to the sentence in light of “the work of creating”. Most English translations ascribe the la-asoting to God; but there is some more recent scholarly work that suggests the verse should read something more like, “all His work that God created to do”, in which it is now creation doing the making. God made things that now do the making. This has beautiful ramifications for our exploration of goodness - God-as-artist did not create a masterwork intended to be frozen in perpetuity like a painting or a marble sculpture, but a generative work the continues unfolding itself as God rests and observes. As creation flourishes, more of God is revealed.

Now with an idea of what Goodness looks like, we can then turn to what Evil is, and how it functions:

Evil is not a created “thing” unto itself, but rather a corruption of what has been called Good by God. Saint Augustine of Hippo called evil a “privation of the good”, which means its a measure of corrupted or missing God-ness. Evil is more akin to a shadow, which exists in this strange liminal space of being a non-thing. Shadows exist conceptually, but they are not something we can pick up, hold, etc. They are a defined absence of something tangible. Now we may realize that Evil, by definition, cannot create; it can only “steal, kill and destroy” (John 10:10); it is anti-creation. The personifications of evil in the satan and his minions are not creatures like you and me, but rather parasitic non-beings that feed off our createdness. To call something evil is to call out the corruption of the good things God has created.

I will now go out on a limb and tell you another creation myth that I think beautifully echoes this understanding of good and evil from the legendary writer JRR Tolkien. While he was resistant to reading his work as religious allegory we cannot help but see how his devout Catholic faith permeated his world-building.

In the beginning, Eru Illuvatar (The One, Father of All) creates the Ainur (akin to angelic beings) to join him in singing the world into existence. Yet the melody and harmonies of the creative process are ruptured by Melkor (later, Morgoth) who in his impatience and jealousy decides to sing a song that invites cacophony into the mix, thus corrupting the melodies and creating a world filled with strife. Morgoth enters into this world, Arda (wherein lies Middle Earth), and captures elves, mutilating them until they become his servants - the orcs. The way magic operates in Tolkien’s world furthers our ideas of good versus evil - good magic, used by Gandalf, advocates for the flourishing of life; while dark magic, the magic of Morgoth’s servant and heir apparent Sauron, corrupts and destroys.

If the nerdiness is losing you, bear with me.

One of the most poignant scenes in Tolkien’s first book, The Hobbit, may give us inspiration on how we are to perceive our present moment in the shadow of evil while still seeing the God of history act towards goodness.

Bilbo Baggins, an unassuming hobbit, is hired by a troop of dwarves at the behest of Gandalf to act as their thief in the quest to reclaim the Kingdom of Erebor under the Lonely Mountain. Through a series of narrow escapes and unlikely friendships, they find themselves at the gateway to a massive forest that was once called Greenwood the Great. However, as the shadow of Sauron fell upon it, the forest became dark and bewitched, earning it the name Taur-nu-Fuin, or Mirkwood.

Mirkwood, by JRR Tolkien

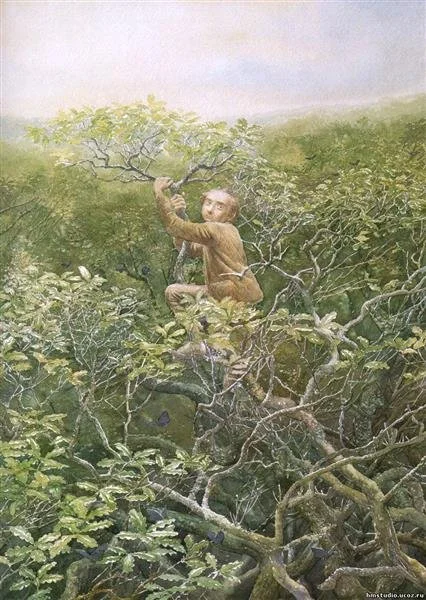

The longer the dwarves and Bilbo wander through the forest, the more the shadow entrances them. They become confused and irritable, straying from the path and turning on one another. In the fog, it is decided Bilbo will climb to the top of one of the trees to get their bearings, else they are eternally trapped in Mirkwood. In the book, Bilbo does so and is initially greeted by fresh air and butterflies, but in his stodgy English way Tolkien determines that Bilbo should not be able to see by the forest because they are, in fact, stuck in a valley. However, in the film adaptation by Peter Jackson, a more positive adjustment is made. Bilbo tastes the clean air, his mind is returned to him, and he sees they are not very far away from their destination at all - the river, the lake, and beyond it - the Lonely Mountain. It is not until the hobbit is able to rise above the bewitchment of the wood that he can see their destination and offer them some direction.

Art by Alan Lee

I believe this scene helps us to remember something so key today when we feel overwhelmed by evil and the corruption of what God has called Good:

When we are lulled to sleep by the evil of the present moment, we must lift our eyes to the horizon to remember what is Good, and where we are heading. How many of us, like the dwarves trapped in the dark forest, feel this daily heaviness upon us? Everywhere we look there is a pervasive fog. Sometimes we have a hard time discerning what is good and what is evil, and we turn upon ourselves or are tempted to give up entirely. In truth, we have to climb up to get perspective - looking back to the beginning of the story to remember God’s good design, and ahead to see our destination. Only then we can climb back down and begin to understand what we advocate for in the present moment - flourishing life, calling out corruption and mutilation of the Good.

Our destination is imaginatively portrayed in the Book of Revelation:

Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,” for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’ or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” (Revelation 21:1-5)

The theologian NT Wright sums it up beautifully in his commentary on this passage: “In the new creation, there is no room for anti-creation.” John gives us a radically unreasonable vision of the end of the story in which God has finished rescuing the world from evil, repairing it stitch-by-stitch. There is no more pain or suffering. Indeed, and this is my favorite element of the final visions of Revelation, God and the Lamb are so close to us that we do not even need the light of the sun to illuminate the way.

What does this final narrative do for you? Does the glimpse of our destination fill you with hope, lift your spirit, and give you courage? Or does cynicism capture your heart, insisting that it is simply too good to be true, and evil will always have the upper hand? Pursuit of justice needs to begin with a conviction of what is “good” in God’s eyes that places us in history with hope.

Almighty and everlasting God, you made the universe with

all its marvelous order, its atoms, worlds, and galaxies, and

the infinite complexity of living creatures: Grant that, as we

probe the mysteries of your creation, we may come to know

you more truly, and more surely fulfill our role in your

eternal purpose; in the name of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.